Are All Bees Hairy?

On this website, you'll find plenty of information about how the hairy bodies of bees help them to collect pollen and transport it back to the nest or hive. However, I was recently asked, 'are all bees hairy?'

This is a great question, especially since many bees visibly have slightly shiny abdomens (tails) and are less furry, whilst other bee abdomens appear to be covered in a thick pile of hair.

Fun fact:

Hairiness is also known as pilosity.

Pilose is the state of being hairy.

Above, this carder bee has a visibly hairy abdomen

Above, this carder bee has a visibly hairy abdomen This short-fringed mining bee has a hairy thorax (upper body), but not so much hair on the abdomen (tail)

This short-fringed mining bee has a hairy thorax (upper body), but not so much hair on the abdomen (tail)Are All Bees Hairy?

Yes, as far as I am aware, all bee species have at least some hair, but some bee species are hairier than others.

In fact, a scientific study measured the hairiness of bees and a number of other pollinators, and in doing so, enabled a comparison between those species.

In the study by Roquer-Beni et al (2020)1, a total of 109 insect pollinator species were measured for their hairiness.

Of the 52 bee species measured for their hairiness, the following were included:

- 20 Andrena (mining bees)

- 5 Osmia (mason bees)

- 1 Anthophora (flower bee)

- 2 Eucera (long-horned bees)

- 1 Xylocopa (large carpenter bee)

- 1 Apis mellifera (western honey bee)

- 10 Bombus (bumble bees)

- 3 Halictus (end-banded furrow bees)

- 8 Lasioglossum (base-banded furrow bees)

- 1 Nomada (nomad bee)

What do bee hairs look like?

Scientists discovered that bees have different types of hair on their bodies many years ago.

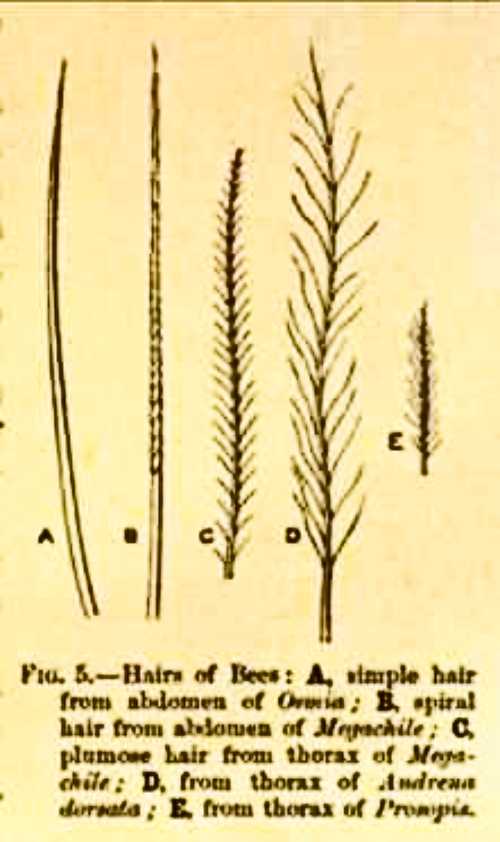

Individual hairs can be simple and smooth, spiral or 'plumose' with branches, as can be seen in the image below, which comes from a book published in 1899 called The Cambridge Natural History2.

Possible hair types found on a bee's body, from The Cambridge Natural History, 1899.

Possible hair types found on a bee's body, from The Cambridge Natural History, 1899.Although the hairs come from different bee species, the authors noted that individual bee species may have different types of hairs on their bodies, for example, simple hairs interspersed with plumose types.

How is hairiness of bees and other pollinators measured?

According to Moretti et al's 'Handbook of protocols for standardized measurement of terrestrial invertebrate functional traits' (2016)2, hairiness is measured by degree of hair coverage, which includes hair length and hair density.

Bees are invertebrates, so in line with Moretti et al's protocol for measuring hairiness, Roquer-Beni et al specifically measured hair length and density (number of hairs per mm2) on the face and the thorax. They then created a 'hairiness index'.

Which bees are the hairiest?

According to Roquer-Beni et al, of the 52 species studied, there were some general observations:

1. Larger bees had longer hair, but the hair of smaller bees was denser than of most other species.

2. According to the hairiness index, of the bees studied, bumble bees (Bombus) were the hairiest, followed by the mason bees (Osmia).

3. Bumble bees had the longest hair, with Bombus hortorum having the longest hair of the Bombus genus that were examined.

4. The bee with the most dense hair was a very small Lasioglossum species - Lasioglossum morio - a bee which measures about 4mm in length. This tiny bee had on average 1052 hairs per mm2.

However, the actual purpose of the study was not to compare all known bee species (the bees selected merely served as a sample) and it is important to note that some groups of bees were missing from the study, such as the leafcutters (Megachile), the plasterers (Colletes), shaggy bees (Panurgus) and Pantaloon bees (Dasypoda).

Are hairier bees better pollinators than less hairy species?

It is known that hairs help to trap pollen, and carry it back to nests, hives and nest cells. As bees visit flowers, they inadvertently transport pollen from one flower to another, enabling pollination to take place.

However, hairiness is not the only factor in pollination. Some, but not all bee species are observed to buzz pollinate.

Other bees are better suited and have a preference for pollinating particular flower shapes, and seasonality also plays a role (availability of bees and pollinators as and when plants and trees are in flower).

Are bees the hairiest pollinators?

Over all, the study by Roquer-Beni et al included other pollinators as well as bees, in particular:

- 52 bee species

- 27 hoverflies

- 2 Bombyliidae (bee-flies)

- 9 other fly species,

- 9 Coleoptera (beetles),

- 5 Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths),

- 3 Vespidae (wasps), and

- 2 Symphyta (saw-flies).

Fox moth - Macrothylacia rubi - female

Fox moth - Macrothylacia rubi - femaleAccording to Roquer-Beni et al, butterflies and moths came top of the hairiness index, having longer, denser hair on average than bees. The butterflies and moths group were followed by bees, hoverflies, beetles, and then other flies.

There were also a number of interesting species observations. For example, the paper wasp Polistes dominulus, had very short but dense hair, with 1444 hairs per mm2, whilst a pollen beetle (Meligethes species) had 1876 hairs!

References

1. Roquer-Beni, L, Rodrigo, A, Arnan, X, et al. A novel method to measure hairiness in bees and other insect pollinators. Ecol Evol. 2020; 10: 2979– 2990. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.6112

2. Harmer, S. F. (Sidney Frederic), Shipley, A. E. (Arthur Everett), Sir, The Cambridge Natural History. 1899.

3. Moretti, M., Dias, A. T. C., de Bello, F., Altermatt, F., Chown, S. L., Azcárate, F. M., … Berg, M. P. (2017). Handbook of protocols for standardized measurement of terrestrial invertebrate functional traits. Functional Ecology, 31(3), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12776