The Leafcutter Bee

Updated: 25th February 2021

Leafcutter bees are solitary species belonging to the Megachile genus of bees, within the Megachilidae bee family. Leafcutter bees are fascinating to watch, and provide a valuable and efficient pollination service for plants.

Spotting leafcutter bees in gardens

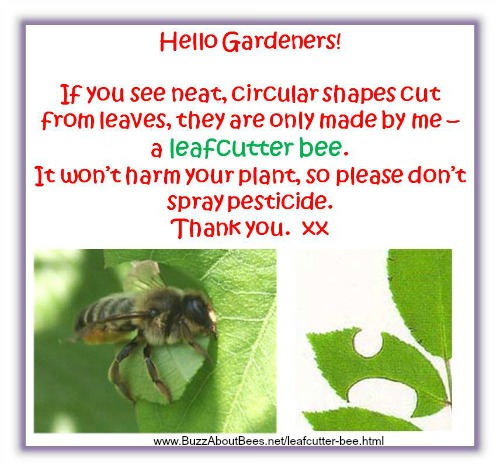

Have you ever noticed little segments cut away from roses, lilac or other shrubs?

If it’s leafcutter bees, there will be a neat crescent or almost circular shaped hole in the leaf. If you should find this, do not worry, usually it will not cause lasting harm to your plants. (Remember, plants survive pruning and dead–heading!). So, please don't spray your plants with pesticides.

Leafcutter bee cutting a neat segment of leaf for constructing nest cells

Leafcutter bee cutting a neat segment of leaf for constructing nest cellsHere is a video taken by Alec Short, showing a leafcutter bee cutting a piece of leaf, then flying off with it (Alec has kindly agreed to allow me to use the video):

Leafcutters always cut away segments of leaf in a very neat, circular fashion. Jagged cuts or rips in leaves are nothing to do with leafcutter bees.

Pollination and leafcutter bees

Leafcutter bees are increasingly recognised for their farm crop pollination service. In fact, the US Agricultural Research Service state that 1 Alfalfa leafcutter bee (Megachile rotundata) can do the job of 20 honey bees! Surprisingly, in research, they discovered that about 150 of these little bees working in greenhouses (or similar) can provide the pollination service of 3,000 honey bees1.

Leafcutter bee life cycle, mating and nesting

Coastal leafcutter bee - Megachile maritima foraging on restharrow

Coastal leafcutter bee - Megachile maritima foraging on restharrow

Males appear earlier than females (protandry), having emerged from egg cells the female parent had positioned nearer to the nest entrance. Males will then begin patrolling for females, ready to pounce and mate with the newly emerged females.

Like mason bees, leafcutters are ‘cavity nesting’. This means they make their nests in ready-made cavities, twigs or in soft rotting wood that can be ‘excavated’.

Upon locating a suitable cavity, females begin gathering segments of leaf which are overlapped and form a series of individual cells in a cylindrical 'cigar' shape. Some species line their egg cells with petals instead of leaves. The silvery leafcutter bee, for example, may use the flower petals of bird's foot trefoil.

A Silvery leafcutter bee

A Silvery leafcutter beeIn each nest cell they lay a single egg, and supply it with pollen upon which the larva can feed once it hatches.

Eggs destined to become females are located toward the back of the nest, those that will develop into males will be positioned at the front. Each cell is sealed up at the end with a further segment of leaf. Nests are small: generally around 4 to 8 inches long.

The larvae pupate and develop inside these cells. They will over-winter in their cells as mature larvae, and emerge as adults the following spring or early summer.

Videos of a leafcutter bees

Below is a small amount of video I managed to capture, of a leafcutter bee female carrying a segment of leaf back to her nest.

It's a very short clip, because I had to lean over some large pots in order to film. This made it difficult for me to sustain filming for a long period of time, so that most of my video clips were very shaky and not at all very good. Anyway, the segment of leaf is carried below the body of the bee, and transported to the nest site - in this case, some hollow canes.

Below is another species of Leafcutter bee: the Carpenter-mimic Leafcutter bee, Megachile xylocopoides. The video was kindly supplied by Tracy L. Elfers of Florida. This bee has used a collection of envelopes and letters as a 'cavity'. The whole process of the bee arriving with a piece of leaf and depositing it into her cells takes about 3 minutes.

Nest usurption in leafcutter bees

I received an interesting email from a Lesley Urquhart,:

"I have one bamboo hole filled by a leaf cutting bee, but the tube next to it has a pile of green material interspersed with pollen lying in front of it, as though the whole nest was ripped out.....It does not appear to be the debris from cutting leaf bits to fit as it has yellow pollen clumps amongst it. Any ideas on what has occurred? The box is protected from birds by a mesh front......

What happened here? The tube to the right is sealed off with green leaves. No other tubes have been filled in this bee box by leaf cutter bees."

With permission from Lesley Urquhart

With permission from Lesley UrquhartMy initial thoughts was that this must be the work of a predator, although it seemed unusual, so on Twitter, I asked an expert from the Natural History Museum in London (please note, I am no longer active on Twitter). This was the response:

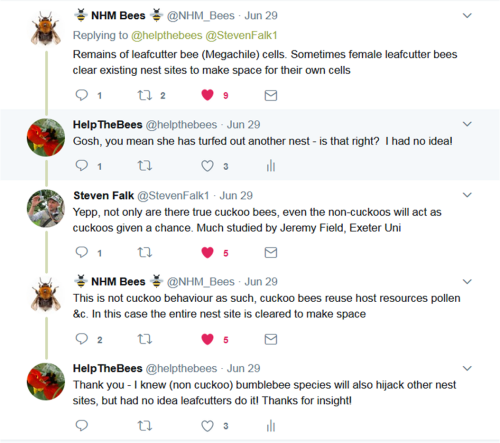

In case you have difficulty reading the tweet from the Natural History Museum in the image, it states:

"Remains of leafcutter bee (Megachile) cells. Sometimes female leafcutter bees clear existing nest sites to make space for their own cells."

I was then told by Steven Falk (author) that it was a form of 'usurption'. I was aware that usurption can happen in bumble bees, (true bumble bee queens may fight over nest sites - this is different from cuckoo behaviour) but had no idea it might be seen in leafcutter bees. Well, you learn something new every day!

Identifying leafcutter bees

Above Megachile willughbiella (Willughby's leafcutter bee) foraging on bedding campanula. The pollen brush is covered in white pollen from the campanula flowers.

Above Megachile willughbiella (Willughby's leafcutter bee) foraging on bedding campanula. The pollen brush is covered in white pollen from the campanula flowers.On first sighting, many species of solitary bee can easily be mistaken for honey bees or even hoverflies. So how can you tell the difference between them, if the leafcutter is not engaged in the activity of cutting leaves or building its nest, but instead, is foraging on flowers?

One give away lies in their methods for collecting pollen. Many other solitary bee species, along with worker honey bees (and indeed bumble bees), collect pollen on their hind legs, then transport it back to the hive or nest.

Leafcutter

bees however, collect pollen on hairs on the underside of their abdomens - their 'pollen brush'. When the bee is carrying pollen, it is often quite visible, sometimes as a whitish cream, pale yellow colour, pale orange or bright orange colour, but when covered in pollen the actual colour of the brush itself may not be visible.

At times when foraging, the pollen brush pokes in the air, and is more easily visible.

Sometimes the pollen brush of the leafcutter bee is easily visible when the bee abdomen is raised in the air whilst the bee forages on flowers.

Sometimes the pollen brush of the leafcutter bee is easily visible when the bee abdomen is raised in the air whilst the bee forages on flowers. Here the actual colour of the pollen brush hairs are clearly seen. However, some species have paler or darker pollen brush hairs.

Here the actual colour of the pollen brush hairs are clearly seen. However, some species have paler or darker pollen brush hairs.

How to attract leafcutter bees

Lots of people would like to be able to watch leafcutter bees in action.

They are fascinating to watch, and in a way, amusing: to see a little bee carrying a piece of leaf as large as itself, or even larger, is wonderful to see!

Leafcutter bees are rather docile, not aggressive.

It’s

possible to encourage them into your garden by providing bundles of

hollow canes, or a log of wood drilled with holes up to 1cm in

diameter (don’t use varnish, preservatives or any other chemicals).

Ref 1: http://www.ars.usda.gov/is/pr/1997/970820.htm