Eusociality In Bees

Sociality in insects spans a broad spectrum, from non-social, solitary species, (for example, in which a fertilized female lays an egg in a suitable cavity, provisions it with food, then plays no further role in the development of her offspring), to vast colonies with thousands of individual colony members.

The term ‘social insect’ therefore describes insect species which live in organised groups with one or more egg-laying females, along with other unfertilized female helpers or ‘workers’, for the purpose of raising offspring.

Bees are of course, insects.

Bumble bees in a nest

Bumble bees in a nestAmong the insect order Hymenoptera, some bee species are social, as are a number of wasps, as well as hornets and ants.

Sociality is also seen in other insect orders (for example, termites in the insect order Blattodea).

What Is Eusociality, And What Is The Difference Between Social And Eusocial Bees?

The terms ‘social’ and ‘eusocial’ can cause confusion, especially when both are used in relation to a particular species or genus.

However, the term ‘social bees’ is the umbrella term for all bees which exhibit social behaviours, regardless of the level of social cooperation displayed.

The term ‘eusociality’ in bees simply describes a particular advanced type of sociality in which a sterile female worker caste assumes responsibility for feeding and maintaining the offspring of the egg-laying female (usually the mother of the female workers) and nest of the colony.

Other examples definitions of 'eusociality' are as follows:

“Eusocial: Cooperative brood care with a reproductive division of labour between generations; in bees, this means the workers are typically daughters of the queen”.

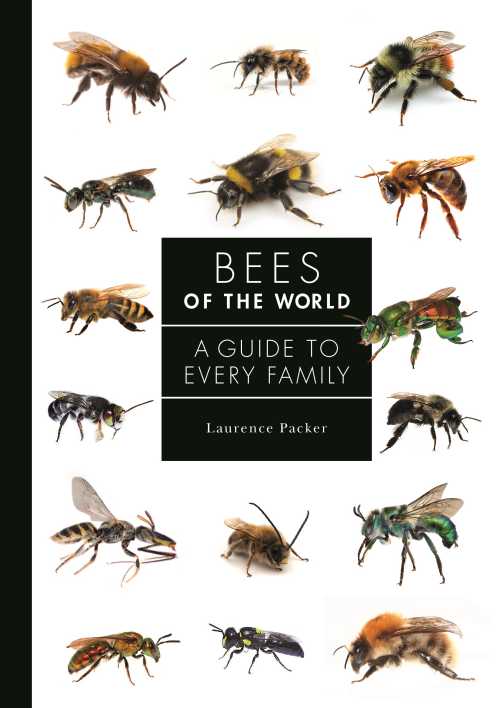

- L. Packer, 2023 - Bees of the World

“Insects that use non-fertilised and often sterile females to help serve one or more reproducing queens, through assorted duties such as foraging, care of grubs, nest defence, nest building etc.”

– S. Falk, 2015 - Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland.

How many bees are eusocial?

In 2003, Goulson4 noted that approximately 1000 bee species are classed as eusocial, but also remarked:

“although the distinction between primitively social species and eusocial species is sometimes blurred”.

What does it mean for a bee to be 'eusocial'?

Eusocial bees are at the pinnacle of sociality1.

For instance, an example of a eusocial bee is the honey bee (Apis genus), which it is widely agreed, exhibits the highest, most complex form of eusociality in bee species1,2,3.

Honey bee workers with queen

Honey bee workers with queenWhy?

The honey bee colony is a sophisticated superorganism, and its interdependent colony members exhibit advanced social behaviours, as well as some other particular characteristics not always apparent in other social bee species, for example:

- The queen cannot survive without her

workers. She does not forage for food,

and cannot start a new colony on her own. Egg cells are built and maintained by

workers.

Workers are infertile, and although workers may sometimes lay eggs (that could only develop into males), this behaviour is usually kept in check by sister workers.

(In other social bee species, such as Bombus (bumble bees) the queen can survive without her workers. She is the colony foundress, forages for food, and builds the first nest cells in which she lays eggs and rears her offspring without assistance). - Healthy honey bee colonies are perennial, and a queen may

live several years before she is removed by the workers or through other

causes.

In natural colonies, new queens are reared by workers from eggs laid by the old queen. - Highly sophisticated communication forms are present, which help to regulate the performance, behaviour and task division within the colony, and activities such as swarming and foraging (including the waggle dance).

Honey bee swarm

Honey bee swarmAre bumble bees eusocial?

Scientist do not always entirely agree as to where bee species might fit on a scale of sociality.

For example, Benton6,7 simply describes bumble bees as 'eusocial'.

An active colony of bumble bees - inside a bee nest.

An active colony of bumble bees - inside a bee nest.For others, the term 'eusocial' is divided further into 'primitively eusocial' and 'advanced eusocial'.

In his 2021 paper, da Silva3 [citing Cowan (1991), Wilson, (1971); Michener, (1974); Eickwort, (1981)] defined them as follows:

Primitively eusocial:

Colonies are small and short-lived,

and morphological differences between reproductive and non-reproductive females

are minimal or non-existent.

Advanced eusocial:

Colonies are large and complex and often

long-lived. Reproductive castes are

often morphologically distinct from non-reproductive castes.

Within these definitions, da Silva places the Bombus species he references into the 'primitively eusocial' category.

Other authors such as Wilson and Messinger-Carill, concur that bumble bees generally belong in the 'primitively eusocial' category1.

However, in 2003, Goulson4 noted that whilst bumble bees are often described in this way because their social organisation is simpler than that of honey bees, he believes that “the tag of ‘primitively social' is probably misleading".

Bombus atratus

Bombus atratusGoulson suggests that although in most bumble bees species, the colony is founded by a single queen and has an annual rather than perennial life cycle, he cites a paper by Garofalo (1974).

Garofalo described a tropical species, Bombus atratus, with perennial colonies and where new colonies are founded by swarming.

It's perhaps fair to state that not all bees in the same genus exhibit the same level of sociality.

When did eusociality evolve in bees?

In the case of corbiculate bees (those with pollen baskets on the hind legs, such as honey bees and bumble bees), it is suggested that eusociality evolved in the late Cretaceous or earlier (over 65 million years ago)8.

Eusociality in halictid (sweat) bees most likely originated approximately 20–22 million years ago, according to Brady et al8.

References

1. Wilson & Messinger-Carril; The Bees In Your Backyard, Princeton University Press 2016.

2. Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland by Steven Falk, Bloomsbury 2015.

3. da Silva J (2021) Life History and the Transitions to Eusociality in the Hymenoptera. Front. Ecol. Evol. 9:727124. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.727124

4. Goulson, D. 2010. Bumblebees, Behavior and Ecology. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, U.K1.

5. Bees of The World: A Guide To Every Family, Laurence Packer. Princeton University Press, Princeton & Oxford, 2023; ISBN: 798-0-691-22662-0.

6. Benton, Ted. Bumblebees: The Natural History & Identification of the Species Found in Britain. Collins 2006, pg 18.

7. Benton, Ted, Solitary Bees, Pelagic Publishing 2017, pg 73.

8. Brady SG, Sipes S, Pearson A, Danforth BN. Recent and simultaneous origins of eusociality in halictid bees. Proc Biol Sci. 2006 Jul 7;273(1594):1643-9. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3496. PMID: 16769636; PMCID: PMC1634925.