How Do Bees Clean Themselves, Each Other And The Nest or Hive?

Bees may come into contact not only with flowers, but also soil and other dirt, mites, parasites, and fungi. Their nests or hives may also attract dirt and mites, and bacteria from, for example, other dead or decaying matter in the nest.

In view of this, you may be wondering how bees keep clean, whether or not they clean each other, and how they clean out their nests or hives.

How do bees clean themselves and why?

All bees clean themselves using their legs to groom dirt away from the body and body parts, including head, face, thorax, abdomen and wings.

In general, bees need to keep their whole bodies clean and free from infection caused by disease-laden fungi and parasites.

However, the antennae are particularly important, because they help bees taste, communicate and pick up sounds.

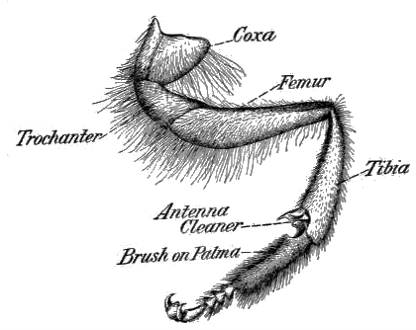

In fact, all bees even have specially adapted antennae cleaners on their front legs, which are a kind of groove shaped a little like a curved pallet knife. These antennae cleaners vary slightly in shape depending on the species of the bee.

Below is an image of the leg of a honey bee, showing the antennae cleaner.

Do bees clean other bees?

But what about when bees have a stubborn parasitic mite or other dirt that is difficult to remove? The research that I am aware of concerns honey bees rather than bumble bees or other wild species.

It turns out that in such circumstances, honey bees may clean each other using their mouths, and this is called 'allogrooming'.

To an extent, I have covered this elsewhere, when I previously wrote about how a breeding programme by the University of Purdue was focussing on rearing Varroa resistant hygienic honey bees which can efficiently tackle the dreaded and deadly Varroa mite.

Hygienic honey bees deal with the Varroa mite by grabbing it and biting it, hence killing the parasite. By picking off the mites they see on other colony members or lurking within the nest or hive, they help to protect the whole colony from deadly infestation and infections spread by Varroa.

You can watch the Purdue University video below.

However, we may wonder how it’s possible that some worker honey bees can tackle the Varroa mite at no risk to themselves – why don’t they get the mite, or at least, contract a disease after biting it and dealing with the pest?

In addition, given that different worker honey bees develop and move through a variety of colony roles depending on the age of the individual, do some honey bees focus specifically on the task of allogrooming?

This topic has been the subject of study by scientists keen to understand whether some Apis mellifera workers (Western honey bee) had highly specialized phenotypes that help them to be efficient allogroomers, and whether these bees had particularly strong immune systems that protected them from potential infections.

Note: A phenotype = a set of characteristics or traits.

The authors of the study, Cini et al(1) note that

“In Apis cerana, allogrooming is performed at a high rate and appears to be a particularly effective counter-adaptation against the major worldwide threat for honey bee colonies and apiculture, the parasitic mites Varroa destructor.”

Cini et al found that honey bee workers performing the task of allogrooming do indeed have some traits in common.

Age of workers

Firstly, allogroomers were generally between the age of 3 to

15 days old, and mostly commonly, within the age range of 6 to 11 days: 76% of

allogrooming events were observed in bees within this age range. (Interestingly,

most allogrooming took place in the area of the comb where brood was present, rather

than by the hive entrance and dance area).

Despite performing the task of keeping other bees clean, most of these busy little allgrooming workers nevertheless performed a variety of other tasks along with their cleaning duties.

Stronger immunity

Secondly, allogroomers have a higher degree of immunity

against bacteria than non-grooming worker bees of the same age.

How do we know?

Cini et al exposed the hemolymph (insect version of blood) to bacteria on plates of agar jelly of both allogrooming bees and non-grooming worker honey bees of the same age.

They found that allogroomers have better immune systems that protect them from risk of infection of disease spread by the mites, as shown by the lower levels of bacterial infection on the hemolymph (blood) of allogroomers.

How do bees know to clean (groom) other bees?

In a honey bee colony, there are thousands of bees, and upto 50-60,000 bees at the peak of the colony life cycle (including workers and drones).

Therefore, it would surely be advantageous for allogroomers to be able to detect nestmates needing to be groomed. It could be that workers wanting to be groomed perform a dance.

Citing Land and Seeley(2), Cini et al comment:

"Indeed, grooming is sometimes solicited through the so called “grooming invitation dance”, whereby bees shake their whole body from side‐to‐side producing specific vibrations which increase the probability of being groomed by a nestmate."

Threats to natural defenses of bees and pollinators

The recognition of the importance of grooming as a significant defense against diseases and parasites, has only received significant attention in recent years.

However, years ago when I began campaigning for bees, I highlighted how manufacturers of certain neonicotinoid insecticides claimed their products killed termite colonies slowly by hampering the grooming behaviour of termites with sublethal doses of insecticide.

In other words, a tiny dose of poison would not kill the termite immediately, but by hampering the ability of the termite to groom itself, it therefore made them vulnerable to diseases, killing them and the whole colony after several months.

Like termites, honey bees are superorganisms, and it seemed to me back then that anything that could kill a termite colony in such a way, might pose a threat to honey bee colonies and wild pollinators, in a similar fashion. I advocated that marketing materials provided by insecticide manufacturers provided important clues as to the functioning and potency of the poisons, and how they might affect non-target, beneficial or benign invertebrate species.

I am as yet, not aware of any research exploring this topic. I hope this will change, along with regulations for insecticide approval.

How do bees keep their hive or nest clean?

Elsewhere on this website, I have written how dead bumble bees may, from time to time, be seen outside nest entrances. This is a natural part of hygienic behaviour, in which healthy workers within a bumble bee colony will remove dead matter (including former colony members or other dead insects or detritus) from the nest to prevent bacterial contamination.

Some wild bee species create burrows in for example wood, sand, mortar or cliff faces, and have different methods for keeping nests clean.

For example, Colletes species (also referred to as 'cellophane', 'plasterer' or 'polyester' bees) line their nests with a cellophane-type substance which they make from saliva and secretions from a small gland on the abdomen called the Dufour’s gland. This cellophane-like substance is not only strong and resistant to water, it also protects the nest from mold and bacteria.

Below is a photograph of a female Colletes cunicularius, the early or vernal mining bee, which creates nest burrows in sand and sandy soils.

Likewise, honey bees use a sticky, anti-bacterial substance

called propolis to line their nests or hives, and also to ‘mummify’ any dead objects

that would be too difficult to remove by the bees, such as a dead mouse. In such a case, the mouse would be covered

with propolis to protect the bee colony from bacteria generated by the decaying

body. You can read more about this on my

page about propolis.

Below is an image of honey bees working with propolis.

Summary and comment

As with humans, bees need to keep themselves clean and they have evolved various means to do this.

A healthy, unpolluted environment will also help bees to maintain their natural defenses against parasites, mites, and pathogenic fungi and bacteria.

References

1. Cini, A., Bordoni, A., Cappa, F. et al. Increased immunocompetence and network centrality of allogroomer workers suggest a link between individual and social immunity in honeybees. Sci Rep 10, 8928 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65780-w

2. Land, B. B. & Seeley, T. D. The grooming invitation dance of the honey bee. Ethology 110, 1–10 (2004).