Positive Messages To Help Save Bees

Increasingly, the public are becoming aware that not everything they have been led to believe is ultimately true.

In the past, those wrong beliefs may have influenced our purchasing choices, as well as gardening and farming practices, that ultimately shape our environment and the biodiversity within it.

When we examine the claims made and discover they are not based in fact, the truth can become more widely known, and behaviours can change - hopefully for the better!

4 Positive Messages

Here are 4 key positive messages I believe are worth sharing, because they help to change opinions about insects, pesticides and farming:

- Most insect

species are beneficial or harmless.

- In terms of using insecticides, prevention is not

necessarily better than cure (preferably, don't use them at all!).

- Organic methods outperform

traditional farming methods.

- There is no food shortage – certainly not in the

West.

These

messages are simple and can be used as sound bites. Below is

more back up information about each of these positive messages, and why

they are important.

Orange-tailed mining bee feeding on willow catkin.

Orange-tailed mining bee feeding on willow catkin.

Positive Message 1:

Most insect

species are beneficial or harmless.

An

interesting fact was presented at an exhibition in the Natural History

Museum in London when I last went: only 1,000 insect species are considered

‘pests’.

Take into account that there are currently 1,000,000 discovered

insect species.

In other words, of discovered insect species, only 0.1%

(that is, 1 in every 1000) are “not beneficial”.

Or put it an even better way:

999 out of every 1,000 insect species, are beneficial or benign "watchers".

Most of these 999 insects are species you are probably not aware of - (but you've long been 'educated' about aphids, vine weevils, carrot fly and lily beetles!).

Note, I had previously read that the figure for beneficial/harmless insects is 97%. Whichever figure is right, they both put insects in perspective.

Yet look in any gardening magazine around

Spring, read any literature about farming and pest control, or take a

look at the shelves in the average gardening centre, and you could be

forgiven for thinking that at least half, or even most insect species

are a BIG problem for anyone who wants to grow anything – be it flowers,

food crops, or trees and shrubs.

Indeed, I have found these views to

be felt by some of the audiences to which I have given talks about bees.

Bumble bee (and hover fly) on helianthus.

Bumble bee (and hover fly) on helianthus.

Positive Message 2:

In terms of using insecticides, prevention is not

necessarily better than cure (preferably, don't use them at all!).

So

long as we exaggerate the threat of insects and invertebrates as 'pests', there are those who will find justification even in preventative

and successive applications of pesticides, not only in food agriculture,

but in horticulture, for use on golf courses, use by councils in public

spaces, and in our gardens.

We currently live in an age where farmers can use seeds pre-coated pesticides such as neonicotinoids, and gardeners are encouraged to treat pot plants just in case a vine weevil happens to come along.

Here's an example:

A study looking at pollen beetle prevalence (regarded

as a ‘pest’) and the application of pesticides by ADAS (an Agricultural

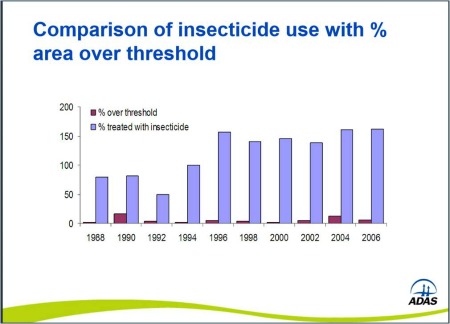

consultancy provider), is very revealing. It shows that farmers in the UK are treating oil seed rape with pesticide quite unnecessarily. The chart below shows 2 things:

- the deep pink columns indicate only tiny levels of infestation by pollen beetle, with only very few cases above the recommended treatment threshold.

- the pale lilac columns show that despite the very low threat, insecticides have been over-used.

(See ref 1 below for source)

But farmers could easily be worried by pollen beetle if they heed press releases and propaganda, such as one found in The Farmer's Guardian (UK magazine) called ‘Pollen Beetle On The Move’ (Ref 2).

Meanwhile,

other evidence suggests oilseed rape crops can recover from loss of buds through pollen beetle, which helps put the

‘danger’ in perspective (ref 3).

Coastal leafcutter bee foraging on restharrow.

Coastal leafcutter bee foraging on restharrow.

Positive Message 3:

Organic method can outperform

traditional farming methods

That’s

the conclusion of a 30 year study by the Rodale Institute,

Pennsylvania. If this is the case, it begs the question, “what kind of

chemicals do we really need to use on our farm land, and how should they be used?”

Positive Message 4:

There is no food shortage – certainly not in the

West.

Some

agrochemical organisations claim that due to impending food shortage,

more chemicals are needed in order to produce more food. However, there

is no food shortage in the developed world, and globally, we waste a

shocking third of food produced every year – mostly in the West. Here

is a quote from a relevant UN study looking at global food wastage:

-

"The results of the study suggest that roughly one-third of food

produced for human consumption is lost or wasted globally, which amounts

to about 1.3 billion tons per year. This inevitably also means that

huge amounts of the resources used in food production are used in vain,

and that the greenhouse gas emissions caused by production of food that

gets lost or wasted are also emissions in vain.”

You can download the UN Study here. (opens new window)

Perhaps we need to look at excess production and distribution, but I struggle to see any justification for increasing intensive agriculture practices.

Red mason bee flying toward wild garlic.

Red mason bee flying toward wild garlic.Of course, some countries genuinely are experiencing

food shortage, due to global trading activity, and climate. What then?

Does this justify inhabitants of poorer countries, spending their money

on more pesticides, weedkillers and so on? Can intensive farming

practice lead to greater food security?

A report concerning

another United Nations study actually suggests that organic methods of

farming would be far more beneficial in, for example, African countries.

Quote:

- “An analysis of 114 projects in 24

African countries found that yields had more than doubled where

organic, or near-organic practices had been used. That increase in yield

jumped to 128 per cent in east Africa.

"Organic farming can often lead to polarised views," said Mr Steiner, a former economist. "With some viewing it as a saviour and others as a niche product or something of a luxury... this report suggests it could make a serious contribution to tackling poverty and food insecurity."

The study found that organic practices outperformed traditional methods and chemical-intensive conventional farming. It also found strong environmental benefits such as improved soil fertility, better retention of water and resistance to drought.”

And so..........

Please spread the word: remember that advertising and marketing rely on spreading key messages repeatedly, and we can all play that game!

Refs:

(1) Download the whole study here: http://www.oregin.info/stakeholders/meetings/shf07-Nov2009/Ellis_ADAS_OREGIN_SHF7_Nov2009_PollenBeetleThresholds.pdf

(2) http://www.farmersguardian.com/home/arable/pollen-beetle-on-the-move/54900.article

(3) (copy and paste into a new window): http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=4775556